Short History of Water Gardening

By Kit Knotts

In researching this article, we found many references that referred to "ancient times" and "long ago", but found ourselves continually looking for a frame of reference. To that end, we have largely used material in this narative, in our Water Gardening Timeline (chronology) and in our Tree (relationships) that gives dates. We feel the sources are credible and links are provided to many of them (with as few ads as possible). Certain events may have occurred earlier but we can find no documentation for them.

The search has taken us through numerous books and articles

and to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of websites. Topics have

included geology, archaeology, paleontology, geography, art history,

religion, politics, architecture, landscape architecture, botany,

horticulture, taxonomy and botanical nomenclature. We are unable

to separate water gardening from any of these because they provide

invaluable perspective.

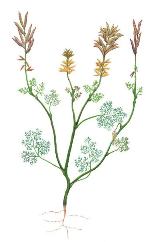

Aquatic plants were among the earliest angiosperms (flowering

plants). Fossil evidence places an early form of waterlily and another aquatic plant (above) 125-115 million years

BCE. One of the most important plants of the world (and an aquatic!),

rice was domesticated 4000 years BCE, based on evidence in Thailand.

The value of many aquatic plants as food cannot be underestimated

but we will look primarily at the ornamental history here.

The "lotus", most likely Nymphaea caerulea and Nymphaea lotus, appears in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics as early as the First Dynasty (2950-2770 BCE). Legends, myths, art and physical evidence bespeak its importance in ancient Egyptian culture and religion. How and when "lotus" Nelumbo reached Egypt is not really known but the Greek historian Herodotus wrote of its presence there in the fifth century BCE.

The earliest planned gardens which included ponds were probably in Egypt, documented as early as 2800 BCE. Decorative ponds and fountains were a major feature in gardens of the Middle Eastern civilizations of Mesopotamia, stimulated by the need for irrigation canals. The design tended to include four water features in the form of a cross, thought to stem from the four rivers of the Garden of Eden and the concept of "flowing to the four corners of the earth". The later Persian and Islamic empires greatly influenced garden design in such nations as Spain and India.

Hinduism had some of its roots in Mesopotamian civilizations as well as in the Indus, where the native Nelumbo was and is today a major symbol in religion. Though its cultivation is not mentioned, we can surmise that it was featured in many gardens. Buddhism, which developed in part from Hinduism in India, also symbolizes the lotus, and made its way to China via the Silk Road.

Lotus seeds were found as a part of the Hemudu Culture in ancient China as long ago as 5000 BCE and presumably were native to that region. Chinese poetry from the Zhou Dynasty (1122-256 BCE) speaks of lotus. The Imperial Gardens developed during the Han Dynasty (from 206 BCE) in China are the first we can find noted for water features.

At about this same time, interest in plants was growing in Greece, though the Greeks were not known for ornamental gardens. The philosopher and botanist Theophrastus wrote De historia plantarum (A History of Plants) and De causis plantarum (About the Reasons of Vegetable Growth). Though it's difficult to tell which plants he was writing about, he can be considered the first botanical taxonomist.

Roman gardens were largely utilitarian though the gardens of the affluent during the Roman Empire assimilated Islamic design, the use of fountains in particular. The collapse of the Roman Empire signaled a virtual end to ornamental gardening in Western Europe until the Islamic conquest of Spain in the eighth century. The pools and fountains of the Alhambra are major examples of that influence as is the Taj Mahal in India.

In 552, Buddhism was introduced to Japan, enhancing the incorporation of water and the lotus in Japanese garden design. Even earlier water was an important element. The lotus first appeared in the art/architecture of Japan in the seventh century.

From the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, Crusaders brought back from the Middle East a desire to create ornamental gardens with water features. The Renaissance brought with it a resurgence of formal gardens in Europe, in Italy especially. Baroque gardens of the seventeenth century included Versailles.

The seventeen hundreds have been called the Golden Age of Botany, partly because wide exploration of exotic lands provided material for a growing group of scientists to study and partly because of Carl Linnaeus, whose Species Plantarum established the system of nomenclature and basis of taxonomy used today. In Species Plantarum, Linnaeus named Nymphaea alba and Nymphaea lotus.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a flurry of Nymphaea species were sent to Europe from around the world, heightening interest in waterlilies and ponds. News of the successful cultivation and flowering of Victoria by Joseph Paxton at Chatsworth in England in 1849 spread far and wide.

This set the stage for the first waterlily hybrids to be made. The first generally accepted as a true hybrid was N. 'Ortgiesiano-rubra' by Eduard Ortgies at the Van Houtte nurseries in Belgium and the second was N. 'Boucheana' by Carl Bouché in Germany. Both of these were night blooming tropicals, created in 1852. William T. Baxter at Oxford Botanic Garden in England introduced a hybrid day blooming tropical, N. 'Daubenyana', possibly as early as 1851, named for Dr. Charles Daubeny.

Though much of the cultivation and study of aquatic plants was going on in England, Belgium and Germany, it was the Frenchman Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac who, at the turn of the twentieth century, created hardy waterlily hybrids that set the standard for all who followed. Another Frenchman, Antoine Lagrange, created wonderful tropical hybrids but almost all of them are lost to cultivation.

Interest in ponds and waterlilies spread to America where Edmund Sturtevant, William Tricker and James Gurney led the way, and Henry S. Conard published his landmark monograph, The Waterlilies, in 1905. George Pring soon made Missouri Botanical Garden the aquatic Mecca of the United States. In the 1930's Martin E. Randig and Otto Beldt introduced their first waterlilies.

This brings us to our contemporary legends of hybridizing and collecting of aquatic plants: hybridizers Bill Frase, Perry Slocum, Johan Harder, Clyde Ikins, Kirk Strawn, Dr. Slearmlarp Wasuwat, Charles Winch; collectors and educators Walter Pagels, Monroe Birdsey and Pat Nutt. And it brings us to the gardens that do so much to showcase aquatics, Kew, Longwood, Missouri, Denver, US National Arboretum, Leiden, Bergius, Gent. All are part of water gardening's past, present and future.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|