VICTORIA

REGIA,

VICTORIA

REGIA,OR

THE GREAT WATER LILY

OF

AMERICA.

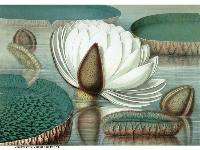

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY WILLIAM SHARP,

FROM SPECIMENS GROWN AT SALEM, MASSACHUSETTS, U. S. A.

BY JOHN FISK ALLEN.

BOSTON:

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE AUTHOR,

BY DUTTON AND WENTWORTH, 37 CONGRESS STREET. 1854.

( Color Images © The University of Kansas Spencer Museum of Art - Click to enlarge )

Description of the Plant | Its Root | Leaves | The Bud | Flower | Blooming | Stamens | Pistil | Seed or Fruit

Page 2 Cultivation in the United States | Temperature and Soils | The Plant in Salem

Conclusion | (Gallery &) Description of the Plates

The great interest

manifested by the public to know somewhat of this Lily has induced

me to prepare this treatise. The Victoria Regia is found distributed

north and south of the Amazon, in the bays and still waters of

the river and its tributaries, in many of the lakes or ponds

of Tropical America, the Berbice River, and various localities

of that section of the continent.

A plant so remarkable, for the rapidity of its growth, the leaves

often expanding eight inches in diameter daily; instances under

my own observation having occurred wherein they have increased,

between sunrise and sunset, half an inch hourly, -- for the beauty

and wonderful construction of these leaves, -- for the ever-blooming

property of the plant, --for the seeming identity, at the first,

of each blossom, yet in reality varying so much as to require

a constant vigilance to detect every distinct characteristic;

-- these and other considerations seemed to justify a careful

and familiar description, accompanied by such appropriate illustrations

as I have been able to procure.

This plant was discovered about fifty-one years ago, by the botanist Haenke, who was sent by the Spanish Government, in the year 1801, to investigate the vegetable productions of Peru, and the fruits of whose labors have been lost to science.

M. A. D'Orbigny says: "When I was travelling in Central America, in the country of the wild Guarayas, who are a tribe of Guaranis or Caribs, I made acquaintance with Father La Cueva, a Spanish missionary, a good and well-informed man, beloved for his, patriarchal virtues, and who had long and earnestly devoted himself to the conversion of the natives. The traveller who, after spending a year among Indians, meets with a fellow-creature capable of understanding and exchanging sentiments with him, can easily appreciate the delight and eagerness with which I conversed with this venerable old man, thirty years of whose life had been passed among savages." In one of these interviews, he mentioned that, with Haenke, he was in a canoe on the Rio Mamore, one of the great tributaries of the River Amazon, when they discovered in the marshes, by the side of the stream, a flower so extraordinary that Haenke fell on his knees in a transport of admiration.

This fact was not made known till nearly forty years afterwards, and it is not a little remarkable that so strange a plant, now known to abound in the still, quiet nooks of most of the rivers in Tropical America, east of the Andes, should not have been noticed by ordinary travellers, in such a manner as to make it recognizable by the reader; and "yet it is without any exception, if we take it as a whole, -- leaves, flowers, size, color, and graceful position in the water, especially when viewed with the usual accompaniments of Tropical American aquatic scenery, -- the most beautiful plant known to Europeans."

M. Bonpland, the fellow-laborer of Humboldt, is the next who had the pleasure of beholding this plant. M. Bonpland says: "In the year 1820, 1 found near the town of Corrientes, and not far from the forks of the Parana and the River Paraguay, a magnificent aquatic plant, known to the natives by the name of Corn or Wheat of the Water." (Mayz de l' Aqua, maize of the water, is so called because it bears fruit filled with seeds which is substituted for grains of maize, and the flour from which is of superior whiteness.) In 1835, he sent seed, to the Garden of Plants, at Paris. "In 1849, when at Rio Pardo," he further says, "I was surprised to see all the ladies equipped with fans, with correct miniature drawings of this Nymphaea, which I described twenty-nine years before." The farina made from the seed is preferred to that from the finest wheat, and the ladies of Corrientes, when the fruits are ripe, obtain the seeds and extract the flour; with this they make pastry, etc., and it is considered a luxury to have cakes of the farina of the Victoria Regia.

The next gatherer of this lily is M. D'Orbigny, who, in 1828, sent specimens to the Natural History Society of Paris, gathered in the Province of Corrientes, on a river tributary to the Rio de la Plata. "If," says D'Orbigny, "there exist in the animal kingdom creatures whose size, compared with our own, commands admiration, if we also gaze with wonder on the giants of the vegetable kingdom, we may well feel an especial pleasure in surveying any peculiarly remarkable species among those genera of plants which we had hitherto known of only moderate dimensions."

For eight months he had been investigating that Province, when, on descending the River Parana, and more than nine hundred miles from its junction with the Rio Platte, having in his company two Guarani Indians only, he observed that the marshes on either side the river were bordered with a green and floating surface; the Indians said it was a plant called "Yrupe, literally water-platter. Nearly a mile of water was overspread with huge, round, and curiously-margined leaves, among which glittered, here and there, the magnificent white and pink flowers, scenting the air with their delicious fragrance." The flowers are over a foot across; are, on opening, white, and change to pink, or rose, or purple, with a perfume like the pine apple. The fruit is half as large, when ripe, as the human head, and full of roundish, farinaceous seeds.

Dr. Poeppig is the next traveller who met with it, during a residence in Chili, Peru, &c., from 1827 to 1832. While descending the Amazon River, he beheld some aquatic plants, whose almost fabulous dimensions entitled them to vie with the celebrated Rafflesia, of India, while they far excelled that marvellous production in beauty and inflorescence. He speaks of it as Euryale Amazonica. As the Victoria Regia has been proved perennial, and the Euryale annual, the name is unquestionably inappropriate.

After a period of

five years, Sir R. H. Schomburgk discovered this plant in British

Guiana, and its introduction into cultivation in England, on

the continent, and this country, is owing to his efforts. Not

knowing of his predecessors' discoveries in other rivers, he

addressed a letter to England, giving an account of its discovery.

Five years later, in 1842, Sir Robert again detected the plant

in Rupununi, an affluent of the Essequibo. "In my rambles

through the West Indian Archipelago," he says, "I had

frequently met the white water lily; but the remark of an eminent

botanist, that these floating plants were entirely unknown on

the continent of South America, did not make me expect to find

a representative of that tribe, which, for the superior grandeur

of its leaves, the beauty of its flowers, and its fragrance,

may be classed amongst the grandest productions of the vegetable

world. It was on the first day of January this year, while contending

with the difficulties nature opposed in different forms to our

progress up the River Berbice, in British Guiana, that we arrived

at a point where the river expanded and formed a currentless

basin. Some object on the southern extremity of this basin attracted

my attention. It was impossible to form any idea what it could

be, and, animating the crew to increase the rate of their paddling,

shortly afterwards we were opposite the object which had raised

my curiosity. A vegetable wonder! All calamities were forgotten.

I felt as botanist, and felt myself rewarded. A gigantic leaf,

from five to six feet in diameter, salver-shaped, with a broad

rim of light green above, and a vivid crimson below, resting

upon the water. Quite in character with the wonderful leaf was

the luxuriant flower, consisting of many hundred petals, passing

in alternate tints from pure white to rose and pink. The smooth

water was covered with them, and I rowed from one to the other

and observed always something new to admire. The leaf on its

surface is of a  bright

green, in form almost orbiculate, with this exception opposite

its axis, where it is slightly bent up. Its diameter measured

from five to six feet; around the whole margin extended a rim

about three to five inches high, on the inside light green, like

the surface of the leaf; on the outside, like the leaf's lower

part, of a bright crimson. The ribs are very prominent, almost

an inch high, radiate from a common centre, and consist of eight

principal ones, with a great many others branching off from them.

These are crossed again by a raised membrane, or bands at right

angles, which gives the whole the appearance of a spider's web,

and are beset with prickles; the veins contain air-cells, like

the petiole and flower stem. The divisions of the ribs and bands

are visible on the upper surface of the leaf, by which it appears

areolated. The young leaf is convolute, and expands but slowly;

the prickly stem ascends with the young leaf till it has reached

the surface - by the time it is developed, its own weight depresses

the stem, and it floats now on the water. The stem of the flower

is an inch thick near the calyx, and is studded with sharp elastic

prickles, about three quarters of an inch in length, The calyx

is four-leaved, each upwards of seven inches in length and three

inches in breadth - at the base they are thick, white inside,

reddish brown and prickly outside. The diameter of the calyx

is twelve to twenty-three inches; on it rests the magnificent

flower, which, when fully developed, covers completely the calyx

with its hundred petals. When it first opens it is white, with

pink in the middle, which spreads over the whole flower the more

it advances in age, and it is generally found the next day of

pink color. As if to enhance its beauty, it is sweet scented.

The petals next to the leaves of the calyx are fleshy, and possess

air-cells, which certainly must contribute to the buoyancy of

the flower. The seeds of the many-celled fruit are numerous,

and imbedded in a spongy substance. We met them hereafter frequently,

and the higher we advanced the more gigantic they became. We

measured a leaf which was six feet and five inches in diameter,

its rim five and a half inches high, and the flower across, fifteen

inches."

bright

green, in form almost orbiculate, with this exception opposite

its axis, where it is slightly bent up. Its diameter measured

from five to six feet; around the whole margin extended a rim

about three to five inches high, on the inside light green, like

the surface of the leaf; on the outside, like the leaf's lower

part, of a bright crimson. The ribs are very prominent, almost

an inch high, radiate from a common centre, and consist of eight

principal ones, with a great many others branching off from them.

These are crossed again by a raised membrane, or bands at right

angles, which gives the whole the appearance of a spider's web,

and are beset with prickles; the veins contain air-cells, like

the petiole and flower stem. The divisions of the ribs and bands

are visible on the upper surface of the leaf, by which it appears

areolated. The young leaf is convolute, and expands but slowly;

the prickly stem ascends with the young leaf till it has reached

the surface - by the time it is developed, its own weight depresses

the stem, and it floats now on the water. The stem of the flower

is an inch thick near the calyx, and is studded with sharp elastic

prickles, about three quarters of an inch in length, The calyx

is four-leaved, each upwards of seven inches in length and three

inches in breadth - at the base they are thick, white inside,

reddish brown and prickly outside. The diameter of the calyx

is twelve to twenty-three inches; on it rests the magnificent

flower, which, when fully developed, covers completely the calyx

with its hundred petals. When it first opens it is white, with

pink in the middle, which spreads over the whole flower the more

it advances in age, and it is generally found the next day of

pink color. As if to enhance its beauty, it is sweet scented.

The petals next to the leaves of the calyx are fleshy, and possess

air-cells, which certainly must contribute to the buoyancy of

the flower. The seeds of the many-celled fruit are numerous,

and imbedded in a spongy substance. We met them hereafter frequently,

and the higher we advanced the more gigantic they became. We

measured a leaf which was six feet and five inches in diameter,

its rim five and a half inches high, and the flower across, fifteen

inches."

In 1845, Mr. Bridges discovered the Victoria in Bolivia. "On one occasion," he says, "I had the good fortune, while riding along the wooded banks of the Yacuma, a tributary of the Mamora, to arrive suddenly at a beautiful pond, or rather small lake, embosomed in the forest, when, to my delight and surprise, I descried, for the first time, the Queen of Aquatics, Victoria Regia! There were at least fifty flowers in view. They grow in four to six feet of water; each plant generally sends but four or five leaves to the surface, yet these cover the water in those parts where the plant abounds, touching one another so closely that I observed a beautiful aquatic bird walking with perfect ease from leaf to leaf."

Since 1845, it has been met with several times by travellers. Previous to that year, all who had met with this plant bad come upon it unexpectedly.

In 1849, Mr. Spruce, a zealous naturalist, made a successful voyage up the Amazon in pursuit of it, and from Para, in November of that year, he sent flowers and leaves, preserved in spirits, to England. Having been told that a plant, answering to the description of the Victoria Regia, was growing in a lake on the largest island, at the junction of the rivers Amazon and Tapayoz, he planned an excursion in search of it. After arriving at the island, the ground was found covered with rank grass and rushes to the depth of six feet, and quite impassable. A little further down, in a small tide river communicating with the lake, which he was attempting to reach by this stream, was discovered the plant itself. Wading into the water, leaves and flowers were thus secured. The largest leaves measured little more than four feet across, but he was told they were much larger in winter, yet they were growing as close as they could lie, in about two feet of water. During the rainy season, the river would be much higher, the surface wider, and the plant doubtless would expand. Mr. Spruce says: "The aspect presented by the Victoria, in its native waters, is so novel and extraordinary that I am at a loss to what to liken it. The similitude is not a poetical one, but assuredly the impression the plant gave me when viewed from the bank above, was that of a number of green tea-trays floating, with here and there a bouquet protruding between them but, when more closely surveyed, the leaves excited the utmost admiration from their immensity and perfect symmetry. A leaf, turned up, suggests some strange fabric of cast iron, just taken from the furnace, -- its ruddy color, and the enormous ribs with which it is strengthened increasing the similarity."

EURYALE AMAZONICA (pronounced Eu-ry'-a-le, signifying a fury) was the name first given to this plant by Poeppig, he thinking it identical with Euryale of the East Indies. Botanists have now no doubt that it is distinct in its characteristics.

VICTORIA REGINA, so called by an error of the press.

NYMPHAEA VICTORIA, so called by Schomburgk, he supposing it to be a Nymphaea, which it has proved not to be.

VICTORIA CRUZIANA. D'Orbigny.

VICTORIA REGIA has been proved by Dr. Lindley to be a distinct and well-marked genus; and notwithstanding Schomburgk (whose successful efforts caused this plant to be introduced into cultivation) named it Nymphaea Victoria, Dr. Lindley, who in 1837 printed a book descriptive and illustrative of the plant and flowers, proposed that Victoria be appended in the usual way of a distinct genus. He therefore gave the name Victoria Regia, and this is now the established and adopted one.

Schomburgk, in his British Guiana, says that he discovered this lily on the first day of January, 1837, one hundred and twenty miles from the coast. "An account of this having been sent to England, Dr. Lindley found it to be a new and well-marked genus, and gave it the name Victoria Regia."

Sir R. H. Schomburgk, the discoverer of the plant in British Guiana, by his own exertions and aided by his friends there, made unsuccessful attempts to introduce living plants into England. The first seeds imported there, that germinated, were packed in moist earth in a bottle. This was in August, 1846. Two plants only survived till winter, when they perished.

On the 28th February, 1849, Dr. Hugh Rodic and Mr. Lachie, of George Town, Demerara, procured seeds which they forwarded to Sir W. J. Hooker, in phials of pure water, agreeably to that gentleman's directions. By the 23d of March, seeds sown in earth, in pots immersed in water, and enclosed in a small glass case, with a tropical temperature, vegetated. These were distributed, and came to perfection first at Chatsworth, the seat of the Duke of Devonshire; next at Syon House, the Duke of Northumberland's; and subsequently at Kew. At the present time, plants have been successfully grown in several botanical gardens in Great Britain, and on the continent of Europe.

Sir Joseph Paxton prepared an account of the growth of the plant under his care, at Chatsworth, for a memoir of the Victoria Regia by Sir W. J. Hooker, and it is on this work we mainly rely for the correctness of our historical materials, a condensed account of which is here given for comparison with plants grown in the United States: --

"The Victoria Regia is, in my opinion, decidedly a perennial plant. After receiving our young plant from the Royal Gardens at Kew, on the third of August, 1849, it was placed in a pot full of water, and plunged in a bed heated to 85°, until the larger tank was ready for its reception, which was on the 10th of August. It was then turned out of the pot into a hillock of prepared soil in the centre of the tank, which in the short space of seventy-nine days, it had completely filled, its dimensions being eighteen feet eight inches by nineteen feet one inch. Calculating by the size of the box it arrived in, which was thirteen inches square and afforded ample space for it, and the size of the tank filled, it must have added daily to its size the almost incredible number of six hundred and forty-seven square inches. This may be considered the most remarkable instance of the rapidity of vegetable development we have on record.

"Early in November, the leaves being four feet eight inches in diameter, and exhibiting every appearance of possessing great strength from the deep thick ribs, which form the foundation of the blade, I was desirous of ascertaining the weight which they would bear, and, accordingly, placed my youngest daughter, eight years of age, weighing forty-two pounds, upon one of the leaves; a copper lid, weighing fifteen pounds, being the readiest thing that presented itself, was placed upon it in order to equalize the pressure, making together fifty-seven pounds. This weight the leaf bore extremely well, as did several others upon which the experiment was tried, their diameter being four feet two inches to four feet nine inches.

"The plant continued to increase in size until the 11th of November, when it perfected its largest leaf which was nearly five feet in diameter, with the edge turned up full two inches, showing the dark purple color of the under side of the leaf, and forming an agreeable contrast with the beautiful yellow-green of the upper. This edge the leaves preserve for about a month, and after that gradually become flat, and this edge is generally the first portion of the leaf to decay, unless the decay is occasioned by some internal constitutional disease, which generally occurs more or less in the dull months of autumn and winter. At those seasons the decay appears in spots on various parts of the surface. The young as well as the old leaves are liable to this disease, which should be immediately taken out with a sharp knife to prevent its spreading. The time, from the first appearance of the leaf to the perfect development, averages from nine to twelve days, and to their decay, six to eight weeks.

"From the l1th of November, the plant began to decline in growth, and its smallest leaf was formed on the 25th of December, which was two feet and half an inch in diameter. After this period, the plant began to show symptoms of reaction, and the leaves to increase in size, although very slowly, until the end of January. It had at that time twenty-four leaves upon it, and with two or three exceptions, all were in a healthy state. This is the greatest number we have had at the same time on this plant. As it progressed, it gave us every reason to believe that the leaves would attain a much larger size this year (1850) than last, and, having the spring in its favor, it grew very luxuriantly, and fully realized our most sanguine expectations. Early in May we were desirous of ascertaining again what weight the leaves were capable of bearing. A leaf was accordingly removed from the plant for the purpose, floated in a brook which runs close to the Gardens, and a very light circular trellis of the same size was made and laid on the surface, so as to distribute the weight equally. We then placed one hundred and twelve pounds upon the leaf, which it bore for some minutes before any water flowed upon it. It would have floated much longer were it not for the difficulty of equally distributing the pressure. The weights were then taken off, and a man, upwards of ten stone weight, stood upon it; this it bore for two or three minutes: after that, a person of eleven stone, which it bore for nearly the same time. This leaf was about five feet in diameter. Since that, we have had both ladies and gentlemen, from eight to eleven stone weight, trying the experiment, and the great buoyant power which they so evidently possess gives the individuals thus standing on them a feeling of perfect safety.

"About the middle of May, a leaf was cut, five feet two inches in diameter, and in July we had several, measuring five feet seven inches in diameter, their edges turning up more than three inches, perpendicularly, and of the most beautiful dark purple color. The flowers, at the same time, measured one foot one inch in diameter. The petioles of the large leaves measured nearly four inches in circumference, and the base of the peduncle three inches.

"About the beginning of August, the plant began again to decrease in size, although gradually - and on the 9th November, which was the anniversary of its first expanding its lovely flowers in this country, it had produced one hundred and fifty leaves, and one hundred and twenty-six flowers. With the exception of a few of the latter, which were removed in bud, with the view of strengthening the plant, it has never ceased flowering front the time of its commencement, and is now (Nov. 27) putting up its flowers with the same regularity as at the beginning, a property which we do not find any other cultivated plant to possess. The leaves are now three feet six inches in diameter, and gradually becoming smaller. The trunk, or root stalk, although it has been twice earthed up, is again out of the soil, and the rootlets, issuing from the base of the petioles, may be easily distinguished. I should say the trunk of our plant would be about five inches in diameter."

In a new house, constructed at a later period, a tank or artificial pond was made, of a circular form, thirty-four feet in diameter, with twenty-six cartloads of prepared soil in the centre, at the bottom, for the roots to grow in. At a yet later period, tanks of more ample dimensions have been, or are being constructed, for the full development of the plant.

The plant at Kew, which was the last to blossom of the three before mentioned, was retarded by a deficiency in the supply of pure water. This difficulty being removed and an ample supply furnished, the plant, in the interval between 20th June and 15th November, produced sixty-five flowers.

Sir R. H. Schomburgk, from the first, considered the Victoria to be a perennial plant - other botanists, from its affinity to Euryale, thought it would prove an annual. From careful observations of Mr. Spruce with native specimens on the Amazon, and from specimens in cultivation in Europe and this country, the matter is fully decided, and no one now doubts its being perennial, like Nymphaea.

For the botanical description of the Victoria Regia, I am indebted to the work of Sir W. J. Hooker, in part, and to the personal inspection of the plant by Rev. J. L. Russell, Professor of Botany to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, and my own observation of the plant in Salem.

From the crown of a large spindle-shaped tuber, and on the appearance of each new leaf, a bundle of many fibrous feeders or rootlets proceeds, which often protrudes above the surface of the soil. These, when young, are of a yellowish, often of a reddish hue. The crown is also surmounted by a series of large scales, which are very apparent as the plant increases in size. There seems to be some intimate connection between these scales and the young leaf and the flower buds, the relative position of which will be referred to hereafter.

Their usual figure is nearly circular, the two alae or wings almost grafted together at the edges, allowing however a narrow groove or channel, and separated only at the exterior of the leaf, somewhat in the form of a notch; a similar notch is seen on the side directly opposite, which is in fact the leaf's apex or summit. Some, on seeing this arrangement, have supposed that it was all intention to drain off the superfluous water which might lodge when the leaf was expanding, an explanation at least doubtful. When in the young stage of growth, and when unfolding the leaf is exquisitely beautiful, equaling, in the estimation of many, the flowers themselves. When fully grown and mature, the texture of the leaf is thin and very tender; its color is of a pale green on the face or disk, but highly colored, and of a purplish crimson tint beneath. The edge or margin is turned up, to the width of from two to four inches, and when the sun shines upon this raised edge in the young leaves, a most beautifully varying crimson color is presented to the eye. Springing from the end of the petiole or leaf-stalk, where it joins the leaf are eight main ribs, which diverge constantly into numerous lesser ones; and these diverging in all directions, strengthened also by arched or curved cross ribs or ties, afford the requisite firmness and support, and exhibit a truly wonderful mechanism. By simply placing a thin board upon the upper surface of the leaf, in such a manner as to equalize the pressure, a full grown man, of one hundred and fifty pounds weight, has been floated upon it; and in many instances, children of eighty pounds in weight have been thus sustained. I have been assured by gentlemen who have witnessed it, that the Indians, when collecting the seed of this plant for food, place their infant children upon the leaves, previously throwing a goat skin upon their surfaces, which, while equalizing the pressure, affords also a dry and safe deposit. Each leaf grows upon its own petiole or stalk, which is penetrated with long and numerous cells, as are likewise the larger and lesser ribs, before mentioned. By this curious arrangement, the perfect buoyancy is maintained. Strong and sharp spines or prickles are thickly set upon the stalk, which extend also over the whole under surface of the leaf itself. Notwithstanding its gigantic size and elaborate structure, the texture of the leaf is so very delicate that should a straw fall perpendicularly from the height of five feet, so as to strike between the ribs, it would penetrate its substance. To render such a tissue, so eminently cellular and thus exceedingly tender and delicate, of a requisite consistence, what better or more wonderful arrangement could have been contrived?

The full grown leaf has been found to measure in winter time, usually, about four feet in diameter, and in midsummer, six or six and a half feet; this last size being the largest that it has been known to attain. During the intervening months, (that is, from August to the last of December) the diameter gradually lessens in extent. From the last mentioned season onward to August, the leaves rapidly increase in size, the largest leaf being produced in the month of July. Many stories of their more extraordinary development may be set down as entirely unworthy of credit.

The flower-bud is of a large size, and when fully grown, just previous to its expanding, it measures from six to nine inches from the base to the tip of the sepals or calyx leaves. Its width or transverse diameter is from three and a half to four and a half inches. Each bud comes from the crown of the root or base of the plant, and at the surface of the soil, and is accompanied by a leaf-bud, which rises with it. I had imagined that they came out enclosed together, but I found that this is not the case. From repeated observation, I have perceived that the leaf issues from the central scale, which closes upon its opposite twin scale, after the leaf has risen a few inches; and there it remains, as before the appearance of the leaf. The flower-bud issues from the outside of this scale, between it and an outer one, and is furnished with a stem (peduncle) of similar character to that of the leaf (petiole), being armed with prickles even to the summit of the bud, the sepals or calyx leaves, even, being spiny. These sepals or calycine leaves are four in number. They are of a deep purple color, fading at the edges into a dull white, thick, coriaceous in their texture, and continuations of the thick, fleshy and prickly calyx tube, which partakes of the same color.

The flowers consist of from fifty to sixty petals in three distinct sets, each growing smaller towards the stamens. The outer petals are, on expansion, of a pure white color, and are from six to seven inches in length. Imagine a most delicate tissue of lace, with the interstices filled with some semi-transparent white substance, yet so soft and tender as to bruise under a slight pressure. This frail and almost gauze-like tissue is soon converted into a filmy paste, when the flower declines upon the surface of the water after it has finished its blossoming.

The buds under my

observation have been, as they approached the moment of bursting,

gradually enlarging at the top, the calyx lobes loosening and

separating from, yet leaving the petals firmly closed. At two,

P.M., the peculiar pine-apple odor has filled the air of the

house, and between the hours of four and five, the petals have

expanded. Frequently one, immediately followed by others, would

suddenly burst off, with a nervous spring, almost at right angles.

By seven, the bud has assumed the appearance of a huge magnolia,

in form and color, but the numerous petals produced a more beautiful

flower. All the flowers have been pure white at this,  the first night of inflorescence, and

they have remained so until the succeeding day has somewhat advanced,

when the outer petals, following the lobes, would reflect, leaving

a central portion, not yet expanded, erect, as seen in Plate

No. 4. At this moment, tinges and rays or veins of pink can be

discovered spreading up and over the white petals, which, before

evening, become quite colored. In this change, however, the flowers

differ, some being more highly colored than others. At meridian,

this reflexed flower again closes, and remains as a partially

opened bud till four in the afternoon, when it again expands,

and at this time, the petals, that formed the upright or central

portion of the reflexed form, spread out, presenting a beautiful

crimson-marked petal upon a pure white; and here no two flowers

can be said to exactly resemble each other, being variously marked.

Sometimes the white ground appears as if the crimson had been

accidentally rained in many different-sized drops upon them,

with here and there a petal upon which the shower descended with

such force as to color the whole. Again, a succeeding flower

will be marked so exquisitely, in such nice lines, and with such

well-defined limits, that you can scarcely realize you are looking

upon the product of the same plant. Between the hours of six

and seven, yet another change comes on; a third set of rigid,

firmer, smaller petals, rise up and stand in an erect position,

yet curved somewhat, opening to view the centre with the golden-colored

stamens, at this moment assuming the appearance of a coronet.

These third petals have sometimes been of a pinkish salmon color,

when first exposed to view; at other times, of a pinkish crimson;

-- when of the former, however, they have soon, by exposure to

the light and air, become of the pinkish crimson.

the first night of inflorescence, and

they have remained so until the succeeding day has somewhat advanced,

when the outer petals, following the lobes, would reflect, leaving

a central portion, not yet expanded, erect, as seen in Plate

No. 4. At this moment, tinges and rays or veins of pink can be

discovered spreading up and over the white petals, which, before

evening, become quite colored. In this change, however, the flowers

differ, some being more highly colored than others. At meridian,

this reflexed flower again closes, and remains as a partially

opened bud till four in the afternoon, when it again expands,

and at this time, the petals, that formed the upright or central

portion of the reflexed form, spread out, presenting a beautiful

crimson-marked petal upon a pure white; and here no two flowers

can be said to exactly resemble each other, being variously marked.

Sometimes the white ground appears as if the crimson had been

accidentally rained in many different-sized drops upon them,

with here and there a petal upon which the shower descended with

such force as to color the whole. Again, a succeeding flower

will be marked so exquisitely, in such nice lines, and with such

well-defined limits, that you can scarcely realize you are looking

upon the product of the same plant. Between the hours of six

and seven, yet another change comes on; a third set of rigid,

firmer, smaller petals, rise up and stand in an erect position,

yet curved somewhat, opening to view the centre with the golden-colored

stamens, at this moment assuming the appearance of a coronet.

These third petals have sometimes been of a pinkish salmon color,

when first exposed to view; at other times, of a pinkish crimson;

-- when of the former, however, they have soon, by exposure to

the light and air, become of the pinkish crimson.

In the coloring shown by the flowers in these last stages, we notice a difference on comparing them with the representations of those that have bloomed in England. I have never seen one with any yellow on the petal, or that had so much of the yellow tinge as is represented in the drawings illustrating the work of Sir W. J. Hooker, a crimson or pure white taking the place of the yellow, and producing a most brilliant flower.

At nine o'clock, P.M., the inflorescence is usually perfected, when the stamens and the interior or under side of the third set of petals assume the staminate yellow color. Soon after ten, the closing process commences, which slowly continues during the successive day, when the outer petals become of a dingy rose color, and the decaying remains sink under the water. A more full description of the blooming will be found in the accounts of the plants of Mr. Cope and others.

"In Nymphaeaceous plants, the stamens are seen passing, by gradations, into petals; but in the Victoria, there is a clearly defined limit between the stamens and petals, best seen in Plates 4 and 5, where a circle of erect petaloid bodies encloses six or seven series of most decided stamens. All these, inserted upon the top or back of the torus, may be looked upon as the staminal crown. The stamens, composing, the innermost rank of them, are sterile, thick, fleshy, lie densely packed nearly horizontally, yet in an ascending direction upon the back of appendages to the stigma, generally one to every two such appendages, and they seem slightly to cohere with them. The next four or five ranks which surround the innermost ones consist of perfect stamens; filaments broadly subulate, red, fleshy, but rigid, bearing the yellowish, linear, two-celled anther on its inner face, below the sharp apex; the cells separated by a narrow connective, and sunk in the substance of the filament. Around these is a rank or circle of petaloid stamens, yellow, tipped with red, and bearing very imperfect anthers. The circle or crown first alluded to, surrounds these, and is quite petaloid, white, (soon stained with yellow,) streaked and spotted with rose color. The filaments of the stamens have air-cells as well as the petals. The pollen grains consist of three or four cohering cells, very pellucid, pale yellow, showing a limbus."

"Ovary, including the tube of the calyx, hemispherical, many-celled, with a very considerable depression at the top, formed by the sessile, concave, or deeply cup-shaped stigma, which has a conical, fleshy column in the centre, as in Nymphaea, and the surface is granulated, and furrowed by a great number of lines, (as many as there are cells to the ovary,) radiating from the centre to the circumference, crenated or toothed at the margin, constituting the stigmatic surface. Immediately at the edge or margin of this stigma is it closely-packed series of remarkable bodies. They seem at first sight to be a continuation of the rays of the stigma, consequently exactly equalling them in number, applied in part to the inner face of the annular torus, to which they slightly cohere, and in part to the inner base of the innermost sterile row of stamens, which lie over them; they are closely packed laterally, compressed, curved or bent at an angle, broad below, tapering to it point above, but it is at the base that they are more firmly attached and less easily separated. Externally they have a thin, membranous integument, quite different from the firm texture of the stigmatic surface adjacent; the back is purplish brown, the sides pale. Internally they are yellowish, laxly cellular, spongy; in age, they appear filled with a loose mass of irregularly formed cells or granules, mixed with stellated filaments or spiculae. A careful inspection of a section made vertically through these bodies and the torus and calyx-tube and germen will show, between the stigma and the calyx-tube, that a mass of the same spongy-like cellular matter is continued to the substance of the ovary, (surrounding the cells,) which is also of the same texture, but less colored. When the flower is past its best, these bodies may easily be separated from the torus, leaving, however, a distinct scar, also visible in the state of the fruit, and covered with the loose, pulpy, granular substance of the interior. In my early description of the Victoria Regia in the Botanical Magazine, I was erroneously led (on an examination of dead specimens) to suppose that these bodies were the stigmas. And more than one eminent botanist have considered Nymphaea as affording something analogous in the incurved points of its stigmas; but these are in reality a prolongation of the stigmatic rays; here, the texture is of a wholly different nature from that of the stigma. The very concave centre of the stigma is occupied by a pyramidical or conoid fleshy column, analogous to what is seen, though on a smaller scale, in the centre of the stigma of Nymphaea alba; a vertical section of this and of the adjacent base of the stigma, when viewed under the microscope, exhibits only very compact cellular structure, the latter having in addition several minute, brown, opaque bodies remote from the surface."

"The fertilized ovary parts with its floral coverings, which decay, except the adherent calyx, and sinks under water to perfect its fruit and ripen its seeds; and again rising to the surface before the seeds are dispersed. The fruit is a very large berry, nearly globose, or rather urceolate-globose, for there is a constriction below the thickened margin, horrid with the copious persistent prickles, of an olive brown color.

"The thickened

corrugated rim is nothing more than the shrivelled, persistent,

annular torus, at the back of which may be observed the scars

of the fallen or decayed sepals and petals, on the top those

of the deciduous stamens; and in the inside of the rim we clearly

discern the impressions left by the bodies which we described

as crowning the margin of the stigma. The annular torus is incorporated

with the whole of the cup-shaped stigma, and the two together

form a large and curious operculum, which eventually separates

from the fruit. Its shape is like that of a wash hand basin;

it is coriaceous and leathery, beautifully fluted and ribbed

within and without, it bears, on the lower edge of the rim, a

portion of the adherent calyx, with a circle of spreading prickles.

Although the falling away of the great operculum might lead to

the idea that such was the mode of dehiscence of the fruit, yet

that is not the case, for the pericarp bursts irregularly, soon

decays, and the seeds are found scattered among the pulp. The

seeds are greenish black, about the size of a pea, oval, with

a slight projection at the upper end. The testa is hard, even

on the surface; albumen copious, farinaceous, milky, and cellular

when young; the embryo small, white, enclosed in a membranous

sack, is lodged at the upper end of the albumen; the cotyledons

are hemispherical, thick and fleshy; radicle short and superior."

A representation of the first growth of the seed is given, the

testa still remaining visible on the surface of the soil under

the water, with the first shoots and earliest leaves, of the

natural size, as they appeared on the plant at Salem.

Description of the Plant | Its Root | Leaves | The Bud | Flower | Blooming | Stamens | Pistil | Seed or Fruit

Page 2 Cultivation in the United States | Temperature and Soils | The Plant in Salem

Conclusion | (Gallery &) Description of the Plates

|

by John Fisk Allen, with illustrations by William Sharp 1854 For shorter download Page 1 | Page 2 | Plates |

||

|

|

||

|

The Gardeners' Chronicle 1850 |

Wisconsin State Horticultural Society 1885 |

Garden and Forest 1888 |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|